The Ways of Paradox: California & Montreal

XXX. [HERMES ON SALE]

Γλύψας ἐπώλει λύγδινόν τις Ἑρμείην.τὸν δ᾿ ἠγόραζον ἄνδρες, ὃς μὲν εἰς στήλην(υἱὸς γὰρ αὐτῷ προσφάτως ἐτεθνήκει),ὁ δὲ χειροτέχνης ὡς θεὸν καθιδρύσων.ἦν δ᾿ ὀψέ, χὠ λιθουργὸς οὐκ ἐπεπράκει,συνθέμενος αὐτοῖς εἰς τὸν ὄρθρον αὖ δείξεινἐλθοῦσιν. ὁ δὲ λιθουργὸς εἶδεν ὑπνώσαςαὐτὸν τὸν Ἑρμῆν ἐν πύλαις ὀνειρείαις“εἶεν” λέγοντα “τἀμὰ νῦν ταλαντεύῃ·ἢ γὰρ με νεκρὸν ἢ θεὸν σὺ ποιήσεις.”

XXXI. [THE MICE AND THEIR GENERALS]

Γαλαῖ ποτ᾿ εἶχον καὶ μύες πρὸς ἀλλήλουςἄσπονδον ἀεὶ πόλεμον αἱμάτων πλήρη.γαλαῖ δ᾿ ἐνίκων. οἱ μύες δὲ τῆς ἥττηςἐδόκουν ὑπάρχειν αἰτίην σφίσιν ταύτην,ὅτι στρατηγοὺς οὐκ ἔχοιεν ἐκδήλους,ἀεὶ δ᾿ ἀτάκτως ὑπομένουσι κινδύνους.εἵλοντο τοίνυν τοὺς γένει τε καὶ ῥώμῃγνώμῃ τ᾿ ἀρίστους, εἰς μάχην τε γενναίους,οἳ σφᾶς ἐκόσμουν καὶ διεῖλον εἰς φρήτραςλόχους τε καὶ φάλαγγας, ὡς παρ᾿ ἀνθρώποις.ἐπεὶ δ᾿ ἐτάχθη πάντα καὶ συνηθροίσθη,καί τις γαλῆν μῦς προὐκαλεῖτο θαρσήσας,οἵ τε στρατηγοὶ λεπτὰ πηλίνων τοίχωνκάρφη μετώποις ἁρμόσαντες ἀκραίοιςἡγοῦντο, παντὸς ἐκφανέστατοι πλήθους.πάλιν δὲ φύζα τοὺς μύας κατειλήφει.ἄλλοι μὲν οὖν σωθέντες ἦσαν ἐν τρώγλαις,τοὺς δὲ στρατηγοὺς εἰστρέχοντας οὐκ εἴατὰ περισσὰ κάρφη τῆς ὀπῆς ἔσω δύνειν.[μόνοι θ᾿ ἑάλωσαν αὐτόθι μυχῶν πρόσθεν]νίκη δ᾿ ἐπ᾿ αὐτοῖς καὶ τρόπαιον εἱστήκει,γαλῆς ἑκάστης μῦν στρατηγὸν ἑλκούσης.Λέγει δ᾿ ὁ μῦθος “εἰς τὸ ζῆν ἀκινδύνωςτῆς λαμπρότητος ηὑτέλεια βελτίων.”

Babrius

*

Turn to the Lesson of St. Eleutherius on the following day. St. Eleutherius is there said to have reigned in the time of the Emperor Commodus who was the son of Marcus Aurelius, and yet we know that Eleutherius reigned before Urban, the order of the popes being Eleutherius, Victor, Zepherinus, Callistus, Urban. It will not do to say that the Marcus Aurelius under whom Urban is placed was not the father of Commodus but a later person of the same name, for the Lessons of St. Cecilia tell us she suffered under Commodus and that Pope Urban was reigning in those days. Besides, according to Eusebius and other historians Urban did not succeed to the Primacy under anybody with the name of Marcus Aurelius, but under Alexander the brother of Heliogabalus.

St. Robert Bellarmine as quoted in the Dubia quaedam de Historiis in Brevario Romano positis [Le Bachelet, Auctarium Bellarminianum, 461-66].

*

Q: You don’t seem to have much use for your fellowman or do many good works.

A: That’s true. I haven’t done a good work in years.

Q: In fact, if I may be frank, you strike me as being rather negative in your attitude, cold-blooded, aloof, derisive, self-indulgent, more fond of the beautiful things of this world than of God.

A: That’s true.

Q: You even seem to take certain satisfaction in the disasters of the twentieth-century and to savor the imminence of world catastrophe rather than world peace, which all religions seek.

A: That’s true.

Walker Percy

*

Hadrian the Seventh Annually: We are Adriano VII ogni anno, or Hadrian the Seventh Annually, based in Florence, a yearly journal dedicated to studying and exploring the works of Fr. Rolfe, an obscure literary figure whose Quixotical life has been studied but whose works have escaped critical attention. Why don’t you tell us about this journal, Mr. Nicolello, and your life and work?

Joseph Nicolello: Baron Augere, if you please — a distinction I picked up in Italy.

HSA: Of course.

BA: The process continues whereby a great deal of what I might under other circumstances offer regular updates on must remain under lock and key. Gone are the days of disseminating literary works and philosophical fragments left and right. As for Fr. Rolfe, he is magnificent in just about every way, and I look forward to offering something when the time is right like an examination of his aphoristic vituperation in the Borgia chronicle. Ideally, I’ll have a simultaneous financial and intellectual hand in the journal, but thinking more long-term I hope down the line to help get Rolfe’s Letters collected, edited, and published in full.

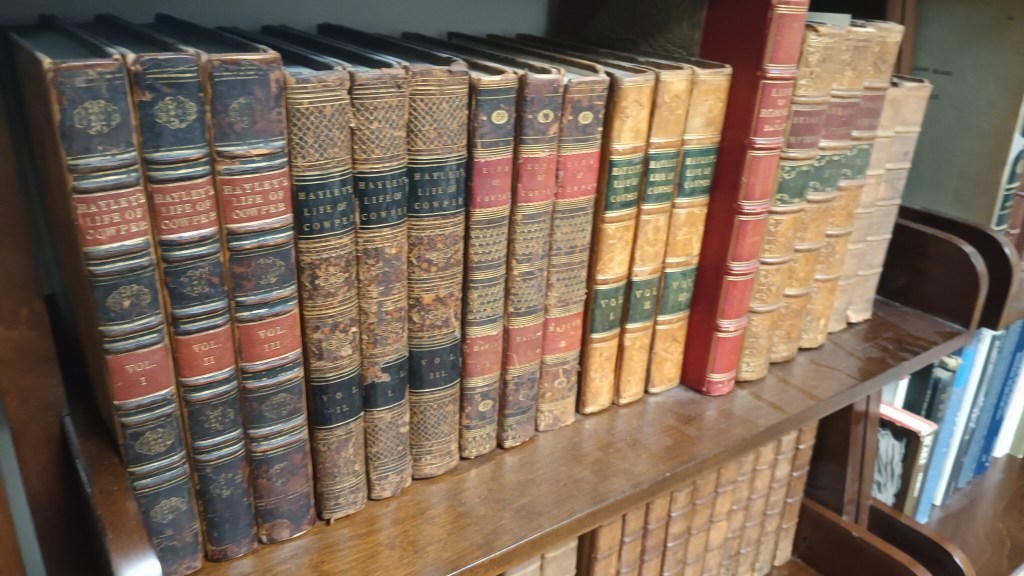

Now as for my life and my work … the beginning and end of my preoccupations in the years ahead shall be a study of the life and works of Robert S. Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald’s Homer translations are famous and have been for some time, I believe his Odyssey was the first paperback used in higher education, but he considered himself first and foremost a poet. He published with New Directions at the time of more familiar names, such as Thomas Merton, Henry Miller, and Ezra Pound. Fitzgerald was very close with both James Agee and Flannery O’Connor, amongst so many more. The Fitzgerald Project is thus my world at present and shall be in the years to come.

HSA: This sounds amazing. But, sir, a monk – even a monk consecrated to Flaubertian aesthetic mysticism – must leave his cell now and then. You are preparing what I envision shall be a major biography, an examine of Fitzgerald’s life, works, and theories of translation … but what do you do in your downtime?

BA: I have been undertaking a five-part sequence of pilgrimage which builds on something which dawned on me recently following sustained rereadings in Nietzsche, Heidegger, various ancient and mystical authors, Auden and Pearson’s voluminous anthology, and Pierre Hadot: literature as a spiritual exercise. I do not care to expound on this or offer a doctrine for it. I have come to reject altogether the mechanisms of deliberation and repetition when it comes to spiritual insight. Rather, I follow the signs of operative grace cast my way from time to time, often out of the hardship of penury and relative serfdom as the Muses would have it, illuminating the process of perpetual researching, writing, teaching; and at present there is an aspect of pilgrimage which is directly corelated to the revelation of literary cognition, which is to say my life.

So the most recent manifestation of this is a fivefold movement which began in California and took me back east, then north to Montreal, and which shall continue into the U.K. as soon as possible, before making it out to Italy, onto France, and from there to walk the Camino Francais, which I believe begins in Paris and ends in Santiago. As soon as I set forth the concept, I am reminded it is subject to change with the wild winds of fortune: thus consider the aforementioned itinerary something like a draft of a draft. Augustine of Hippo did say traveling was like reading, but I would add to this that travel plans are a lot like sketching a literary work of art, or I imagine works of visual art and architecture as well. One begins with a groundwork. Sometimes one takes the groundwork all the way through to the end. Other times the dialectical phenomenology of everyday life has its way. In any case, I am not seeking a spiritual experience, which I think is important, in the same way that one does not want to be a specifically religious or devotional writer. Let one write about biblical exegesis in the mental framework of characters and poetic insights all day long, so long as one is not imprisoned by religious (ideological) categorization. Boxing oneself into a specific type of authorial framework is identical to deliberately never leaving one’s hometown: unless one is Kant, one would be better off to keep quiet. Is there anything more tedious than these wearisome scribblers who never leave their comfort zones, and all seem to love profane literature and films such as The Lord of the Rings? One gets sick simply thinking of such persons; God forbid one actually sat down to read them. Such is like taking advice on global travel from, again, the ones who never leave home. And thus while there is a spiritual essence to my present wanderings and projects, sure, one could also say, instead, that I am in the mood for a good, long walk, as always, and Lisbon – my endpoint, rather than Santiago – calls my name. I think the walk ends in Santiago, but for me the odyssey ends in Lisbon. The idea calls my name, the way the first flash of a line compels the poet to stop what he is doing to get it down. Portugal is a good endpoint for this future movement: I long to step foot in the land of Cesario Verde.

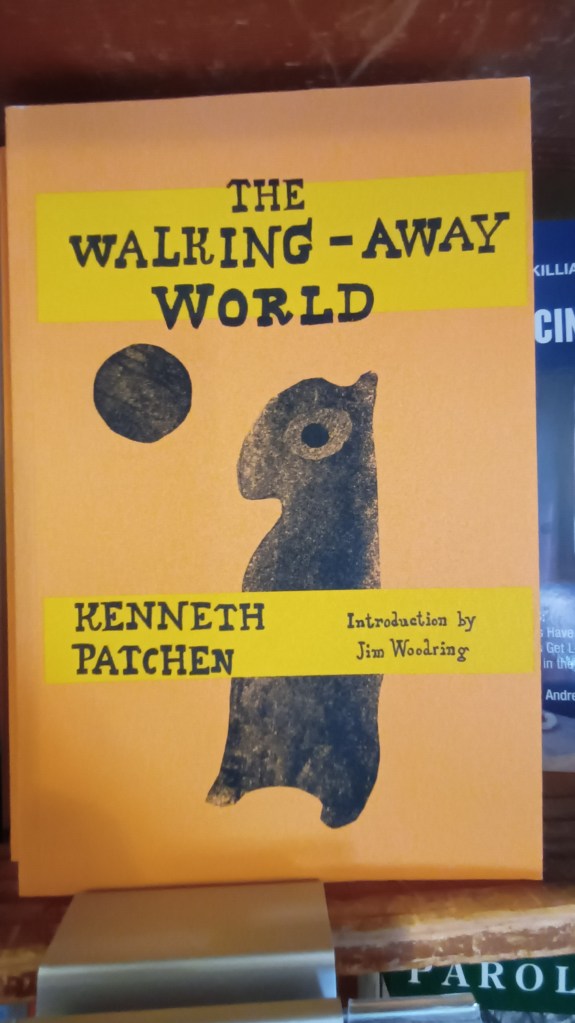

Now when I was in San Francisco last month I was reminded of Fernando Pessoa, as he is in many bookstore windows these days, Pessoa whom I had not read since I was a teenager, or 20 or so. I see he has become quite popular meanwhile! Well, if I am going conclude this apostolic mission of the interior in Portugal, it is going to have something to do with poetry, and for me the hour of Pessoa passed long ago, and now one is aligned with Verde. In a similar way, one might at a certain point grow sick to death of hearing what this, that, or the other person has to say about Dante, and turn to Leopardi. All of this has to do with cultivating time far away from the madding crowds, one of several prerequisites for accomplishing anything worthwhile.

But as for one’s work … I was flattered a couple of years ago that mortals and others (about two of them) were interested enough in my syllogistic novel to touch base with me on it, offer works on syllogism as reference points, and stimulating thoughts. I undertook a debilitating amount of research into the history of syllogistic thinking over the centuries prior to writing 30 or so pages. I prepared the work with a good two years of uninterrupted research … but I fear I did not get very far. Perhaps, as it stands, it is a short story. It could be a novella, no doubt, about one trying to write a novel in syllogisms. But the crisis with the syllogistic novel seems, or seemed, to mark a turning point in my own ontological comprehension of the literary work of art, the history of the concept of time, down unto creative inception.

The same thing happened recently with an idea for an epic poem I was tinkering with – a liberating crisis, if one will – as the years have also seen me spending a great deal of time with John Milton, Vergil in both Latin as well as Fitzgerald’s translation, as well as Fitzgerald’s translations of Homer; but as for my own epic, here I made it about 800 lines in and threw in the towel. I do not know when or if the towels shall be recalled, or if thrown towels are ever retaken or something like that, but in both cases – Syllogistic Novel and Epic – I found that the works were not worth seeing through to the end. This was not a hunch or a feeling, but rather a conclusion reached after years of researching and reading, down to the preliminary narrative executions.

I think that in essence, it boils down to something seldom mentioned in the realm of literary practice and the desire to write certain books: the reward is too nimble to try to configure these things in one’s spare time, especially when one has no spare time whatsoever. A literary work of art depends both on what one is living for, as well as if the work shall be published or is at least intended to be, and so on. The amount of time and energy required to write a destinationless text, what with its hypothetical terminus and all its romantic possibilities, in the end transcends philosophy and language and breaks down into necessitation. Necessitation is by proxy correlated to finitude. A given poetic work is either predestined to land, come what may of it, or it is something more like a mind parasite. The phenomenological process of contemplating a literary work of art before deciding not to go through with it would make for a prescient, if arcane, study, perhaps alongside Schopenhauer’s proposal for a tragic history of literature, wherein we examine case by case, continent by continent, how horribly specific poets and writers were treated in their time, century after century, but who endured to the end, whence death becomes something like the opening gunshot of a downhill motor race, with the same cruel spectators now rushing out to museums, book release events, film adaptations, and so on, of the cursed poet’s glorious work.

Now keep in mind that that is simply the realm or poetry and literary fiction, which over the past couple of years in particular has decreased in importance for me as more refined tasks have increased in both prospect and obligation.

And thus on the academic front, I am working on a biography of Homer translator and poet Robert S. Fitzgerald. I am preparing the scaffold at present, but the work shall be a critical biography, and by this I mean it examines both his life and his works. For some reason his poetry has never received a full, comprehensive examination; nor has his life. My archival work at UCLA and the University of Pennsylvania, in addition to my relentless examinations of O’Connor, Maritain, Agee, and in essence all of 20th c. American poetry, in addition to a lifelong love of Classical Literature, has trained me well for this purpose.

HSA: We are very excited about this. You had said earlier – is there something with Henry James this winter at MLA 2024? William Blake exegesis? Prose poem on the interior life of St Joseph?

BA: Yes, all of the above, though the Blakean exegesis orbits far from the Fitzgerald project. I will likely not resume work on the Blake [Milton: A Poem] exegesis until 2029 or something like that. Joseph Wittreich thought it was perhaps destined to be my most significant scholarly work, so we shall see. The prose poem on St. Joseph’s interior life is already about completed. And as for the talk at MLA, with the Henry James Society, I am very excited about that.

Homer and Milton along with Walter Ong seem to have instilled a lifelong interest in orality and literature for me. I did not think there would be any connections here to my then-incidental readings in Heidegger and the later James. But in the process I began to think of James in a way which concerns orality, the invisible and the visible, ecclesial prose, (I worked on a number of such original translations at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center). and an aspect of Heidegger’s thought that at least for me seems tailormade for reconsidering the later James. To this end I will be giving a talk at MLA 2024 in Philadelphia on Henry James’s The Golden Bowl.

HSA: That is … quite the book. The later James strikes me as quicksand in a dream, yet essential in its link to Pound, et al.

BA: I wanted to read it for a good decade, and at last worked my way up to it after reading many other works by and on James. But the idea for the paper actually came from Heidegger. In his later work The Event, you see, Heidegger makes reference to “The enduring in the saying of the twisting free of the difference into the departure”, which for me at least was, is, an unexpected way of cognizing the narrative and fate of Maggie Verver altogether. In the talk, having both briefly shed light on what Heidegger’s up to in his text and thereafter locating its methodological nebulae in James, I intend to elucidate discreet bits of the text from The Golden Bowl on the event-grounds of catastrophe, trauma, and style.

HSA: Catastrophe?

BA: Catastrophe, in my reading, is a matter of interiority enhanced by subtle and unsubtle religious, symbolic elements of the work such as constant religious language recurring throughout scenes of interior crisis as the affair is inferred, dodged, denied, accepted, imaginatively confronted, as well as the breaking of the golden bowl itself into three parts. The shadows of real-life events give way to a trauma that is subsequently cognized and illumined, thereby heightening the work’s progressively intoxicating style.

In each of these event-arenas, I maintain a philosophical explication of the Jamesian event in terms of the orality and ecclesiology of the text, combining close reading with insights from Walter Ong and R.P. Blackmur, with each event unpacked in terms of an unfolding, surmounting synthesis of interior and exterior event, ecclesiastical linguistic flashes alongside theories in orality and literature, as well as religious experience more generally (I believe a relevant nod to William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience may also help us think more profoundly on the grounds of The Golden Bowl and the orality of literary cognition as it culminates in the events that ignite and maintain Maggie’s interiority and James’s subtle religious language therein).

The talk should lend itself to further correlative interrogation of The Golden Bowl, as well as Wings of the Dove and The Ambassadors.

HSA: I did not know you were so fond of James.

BA: I contain, as it were, multitudes. Here is another thing, in some other news: for reasons that have escaped me ever since I finished it, I wrote a children’s book earlier this year. I cannot bring myself to circulate it. Either the perfect opportunity for illustrative collaboration must arise or I may confine it to the strata of posthumous papers. Although the odds are impossibly slim that anything I do at this point will be widely read, let alone widely celebrated, I think that making my mark as a children’s author of all things might be too insane for my liking.

I noted above I am planning on undertaking the Camino Francais this spring, and also developing a UK tour which shall begin in Wales and end in Ireland. I have been trying to integrate time in Greece, culminating in a journey to Patmos, into the equation, but there are too many uncertain variables at the moment. Things should start coming into a clearer focus in October, and then be very clear in January. I am of course making copious notes on these ongoing and forthcoming odysseys, but as far as a travelogue is concerned I feel far too set within a blend of Thomas More and John Lennon at the present time to realistically even map out such a manuscript. It is possible, but after one does a certain amount for a completely ungrateful public, the whole conception of a “labor of love” morphs into something else. The work one carries out moves into work that firstly makes one a living, and then secondly, the ‘other’ works, move from projects with dreams and hopes attached to them into projects that one dislikes the prospect of dying without having. If one is indifferent to a work made nonexistent in death, one has the first clue as to what one had better not prioritize. One must become – it does not happen overnight, for it is experiential – independent of public opinion in the works one is set out carrying out without them. I have made the mistake now of assuming certain audiences and publics would support given projects of mine, only to abandon me upon its coming into fruition. Indifference of these types, when contemplating works of the heart which are less desires than synonymous with Being: this is, as Hegel might say, the first formal condition of achieving anything great or rational. One wants to interiorly relinquish theoretical outcomes and focus on the work-itself, and to this end specific types of works take predominance depending on the poet or philosopher.

The Fitzgerald biography is another matter entirely: my aim here is to produce as superb a work as possible for as many readers as possible, in homage to a great, hitherto neglected man. To execute the work in such a way likewise pays homage to all of my great mentors and friends who shall have a hand in guiding me at various stages.

HSA: We will be very pleased to learn more – when the time is right, down the line! – about Rolfe’s Letters, and to receive you in Rome!

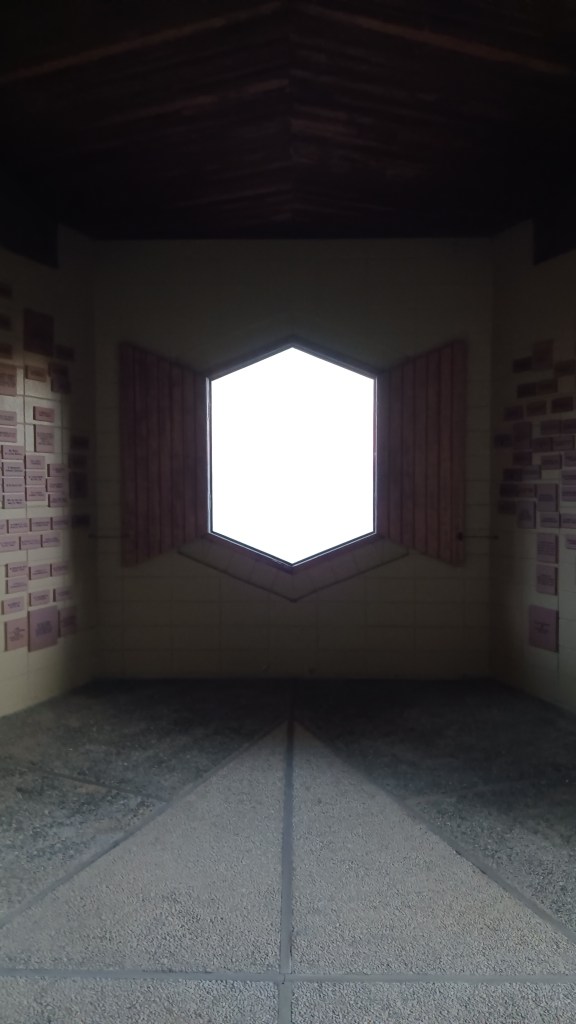

BA: I would have been there this summer, though I spent a good deal of time in Big Sur, enhanced by shorter stays in San Francisco and Montreal. In San Francisco I was researching the place itself; in Montreal I was researching St. Joseph, on whom I am writing a short book, a prose poem, on the mystical nature of his interior life. It is a good thing it is short (and about three-quarters of the way complete), since the Fitzgerald project rightfully demands all of my attention. In Big Sur, I was at the New Camaldoli Hermitage, which I must offer some reflections on sometime … I would heartily recommend visiting there – and for men contemplating a vocation, looking into their Ora et Labora program – without hesitation to anyone for whom such a thing sounds appealing. There are material benefits such as having no wifi or phone service whatsoever which cannot be understated. But there is a certain magic at hand, in wandering the land, in discussions with the brothers, in having one’s life for a time be guided by bells and services. I am very fond of the place and look forward to returning as soon as the stars are aligned.

As I reflect on Big Sur, Monterey, San Francisco, and Montreal, I feel a change formulating within me at a glacial velocity. It has something to do with exactitude and deliberation, in a textual sense certainly … but then I have long been drawn to that Nietzschean concept of life as literature … and then again it also pertains to a certain grave clarity on specific matters, and what a rupture with them means in the relational sense for various nouns, that has been unfolding within me.

A handful of encounters with unrelated persons this year and the synchronicities with which how each case developed and declined has left me with thoughts I cannot shake. In one particular case, the crisis immediately translated into literature. I was distraught over matters such as mechanical faith, repetition and hypocrisy, and the dangers of pity. As I reviewed my notes on the matter an old Stefan Zweig book I picked up but did not finish several years ago came to mind: Beware of Pity.

I was due for a summer read unrelated to the Fitzgerald project. Lo and behold, Zweig opens the text with remarks that were for me beyond prescient, noting that at a certain point characters (and I assume he likewise means by proxy situations or scenarios) deliver themselves to the writer, or poet. One does not need a workshop, or a how-to guide, or a tutorial, on the occasion one has been tried by fire and found prepared, one for whom it is at last directly stated, in the form of the literary imagination and sudden explosions of material which make no sense at first but are quickly revealed indispensable, “My grace is sufficient for thee.”

Nonetheless, there is straightaway a sort of pathological dimension to this idea that persons in particular “appear” to one, that I abhor, along with so much of scientism, opting instead at this point in both manners of science and religion for something not unlike Feyerbrand’s ideas of an anarchy of the imagination overcoming epistemological stagnancy or decay through method in matters visible and invisible, and in the case of the former of course looking at Zweig and seeing a sort of pathological perception of how one goes about literary construction.

Zweig’s preparatory insight has an element of predestination about it which calls to mind the best of Augustine, Calvin, and Perry Miller.

HSA: Have you ever read Schopenhauer on predestination?

BA: How much better off we’d all be if there more Yonah Schimmels in the world, as well as dedicated readers of Montaigne and Schopenhauer.

But to return to Zweig’s insight, I read it in metaphysical sense, and have not been thinking of it everyday by any means, but it is something I cannot shake. Thus, I cannot shake the foundations and disintegrations of relations which underwent an unrelated typological fissure, while at the same time I see in Zweig an explication of something I was feeling whilst being unable to eclipse the vulgar binary of there either being nothing to the experiences, or me being malicious to see in these piercing circumstances, or at least their interrelated epilogues, an occasion for supreme literature. Is this all confusing? Very well: be patient; a fusion of Brooklyn and Athens cometh.

HSA: I notice you said “whilst” just a second ago – should I change it to “while” in the transcript?

BA: No. “Whilst” is simply a matter of taste, not unlike one’s approach to time, death, and eternity themselves.